IACS Computes! 2019

IACS Computes! High School summer camp

Day 1

Day 2

Day 3

Day 4

Day 5

Day 6

Day 7

Day 8

Day 9

Towers of Hanoi

This puzzle was invented by a French mathematician named Édouard Lucas in 1883. The core idea is relatively simple: given three pegs and n differently sized disks, move all the disks from one peg onto another.

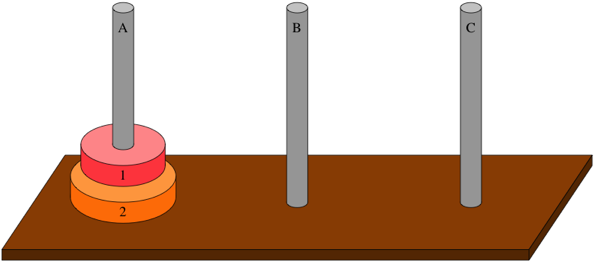

Let our pegs be A, B, and C, and number our disks from 1 to n with 1 being the smallest disk and n being the largest. Initially, all disks are stacked on peg A in decreasing size from bottom to top, such that disk n is on the bottom, and disk 1 is on the top.

Sounds easy, right? Well, not so fast.

We have some rules restricting the movement of our disks:

- You can only move one disk at a time.

- A disk can only go on top of another disk if it’s smaller than the one it would be resting on. For instance, if you want to move disk 2, it has to be on disk 3 or higher.

For a better idea of what this looks like, watch this robot arm figure it out for itself.

Legend has it that somewhere, in some arbitrary Asian country (Hanoi is in Vietnam, but you can find versions of this story about Tibet, India, and other places), monks are solving this problem with a set of 64 disks. It is said that the tower was created at the beginning of time, and when the last movement is made, the world will end. If this is true, then assuming the priests are able to move the disks at a rate of one disk per second, then it would take them a minimum of $2^{64}-1$ seconds to complete the puzzle. That’s 585 billion years - 43 times the current age of the universe.

Solving recursively

First, let’s see how to solve the problem recursively. We’ll start with a really easy case: one disk, that is, $n=1$. The case of $n=1$ will be our base case. You can always move disk 1 from peg A to peg B, because you know that any disks below it must be larger. And there’s nothing special about pegs A and B. You can move disk 1 from peg B to peg C if you like, or from peg C to peg A, or from any peg to any peg. Solving the Towers of Hanoi problem with one disk is trivial, and it requires moving only the one disk one time.

How about two disks? How do you solve the problem when $n=2$? You can do it in three steps. Here’s what it looks like at the start:

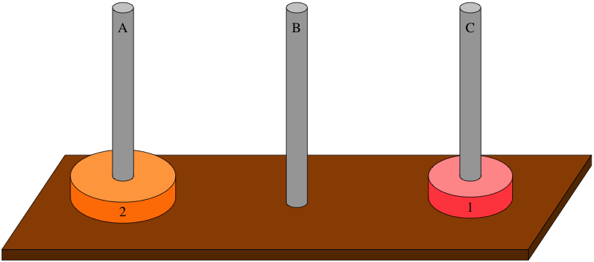

First, move disk 1 from peg A to peg C:

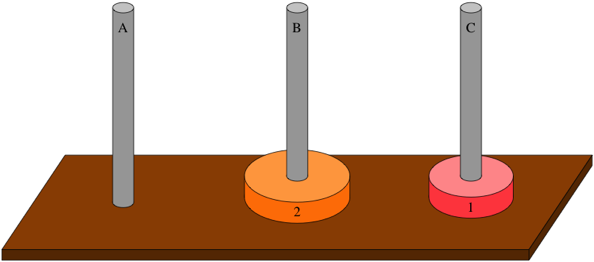

Notice that we’re using peg C as a spare peg, a place to put disk 1 so that we can get at disk 2. Now that disk 2—the bottommost disk—is exposed, move it to peg B:

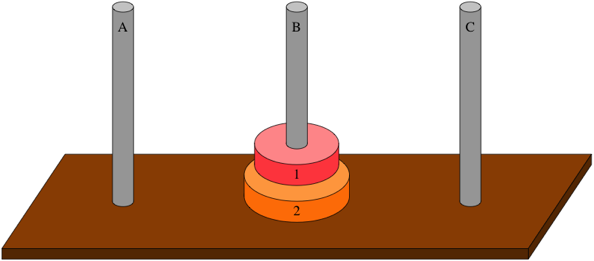

Finally, move disk 1 from peg C to peg B:

This solution takes three steps, and once again there’s nothing special about moving the two disks from peg A to peg B. You can move them from peg B to peg C by using peg A as the spare peg: move disk 1 from peg B to peg A, then move disk 2 from peg B to peg C, and finish by moving disk 1 from peg A to peg C.

Do you agree that you can move disks 1 and 2 from any peg to any peg in three steps? (Hint: Say “yes.”)

Generalize for n and be on your merry way!